The Takeaway

Project & impacts: This multi-year design research project, conducted in an educational program in a women’s prison, led to the discovery of key participant values (e.g. community, care, growth), which were used to collaboratively redesign program curricula. Additionally, relationships forged during the project allowed a version of the program to continue during Covid-19.

My role: Research lead (collaboratively leading design and execution of all research activities); mentor to three junior research collaborators; liaison to program lead, teachers, incarcerated women, and prison staff.

Enhancing Positive Community Among Incarcerated Women

Using a Prison Education Program to Nurture Women’s Ability to Flourish

Background

Although women are incarcerated at lower rates than men, women’s incarceration has grown dramatically in recent decades: over 500% between 1980 and 2021. At the same time, women most often come into prisons after difficult childhoods and limited opportunity: over half, for example, have not finished high school when they enter the system.

In northern Georgia, a group of faculty at a local university started a pre-college certificate program at a nearby state prison for women to help address this need. The program ran successfully for several years, but its founders came to wonder how it could become even better. What about the program was most important to the participants, not just in terms of educational skills, but for helping them build good, flourishing lives? How could the program do this even better? As a PhD student and researcher, I partnered with the program on a multi-year research and design project to answer these questions and make key program enhancements.

Design Challenge

How might we understand the core values of women in a prison-based educational program, and use these to improve the program and participants’ ability to thrive?

Methods Used

Ethnography, Focus Groups, Interviews

Stakeholder Engagement

Presentations & Storytelling

Product Design (activity sheets)

Project Roles

Lead Researcher

Cross-Functional Collaborator

Research Mentor

Process

As a leader in designing and running the research for this project, I collaborated continuously with the program’s founder, teachers, and staff. We relied heavily on the program’s existing relationships with prison officials and incarcerated women, and aimed for the project to only strengthen those ties.

To do this, our process was transparent and cooperative. We got permission from the warden to conduct the research, and explained our goals and process to the women in the program. We made sure to chat and connect with prison staff at every visit, so we were not seen antagonistically as “those elite university people.” The research itself involved ethnography during program hours, individual interviews, demographic surveys, and focus groups about what it meant to the women to live a “good life.”

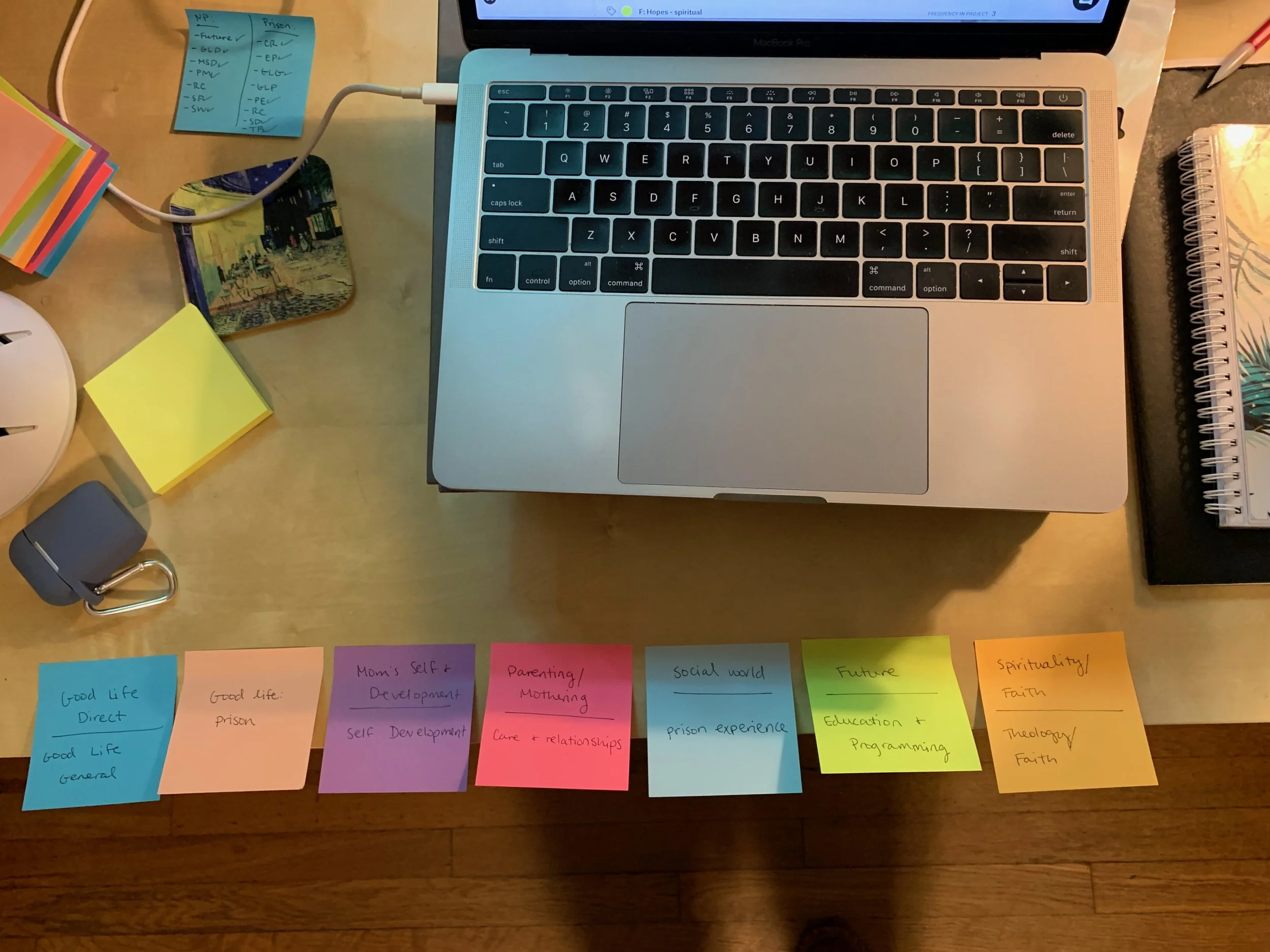

Analysis for the project happened both as a group, as we processed together after a day of research or checked in during team meetings, and individually.

Sitting with our notes and transcripts on my own, I noticed a clear pattern emerging: the educational content was important to the women, but even more important was the trust, care, and relationships they were able to build with other women in the “safe space” of the program.

I brought this to my team, and it became a clarifying, watershed moment. In asking what was most powerful about educational spaces for women inside, we found our answer: community.

In some ways, this was not surprising: the majority of women come into prison with histories of trauma, and prison itself is often an isolating and re-traumatizing space. There is a deep need for opportunities for healthy relationship building and community among women in prison. Re-oriented around this key finding, we shifted our research to conduct focus groups and interviews specifically about the meaning of “care” between women and how the program could encourage it. Some key findings included:

Respect. Students expressed over and over that cultivating a classroom space where they could “feel human again,” and knew they could be themselves, was a crucial baseline for all other program outcomes.

Relational and leadership development. Women talked about how they wanted to build community with others inside, but how it wasn’t always safe (and many had difficulty trusting because of prior trauma). Providing opportunities for relational development in the program, as well as leadership development as women gained confidence and trust, helped them continue to build networks of care and community outside the program.

Commitment. In a system marked by bureaucratic dysfunction and little respect for the dignity of those inside, the women were used to being arbitrarily excluded from programs and to people disappearing with little notice. Contrary to this, they expressed the importance of “leaving no one behind,” and a desire for commitment and continuity from both individuals and programs.

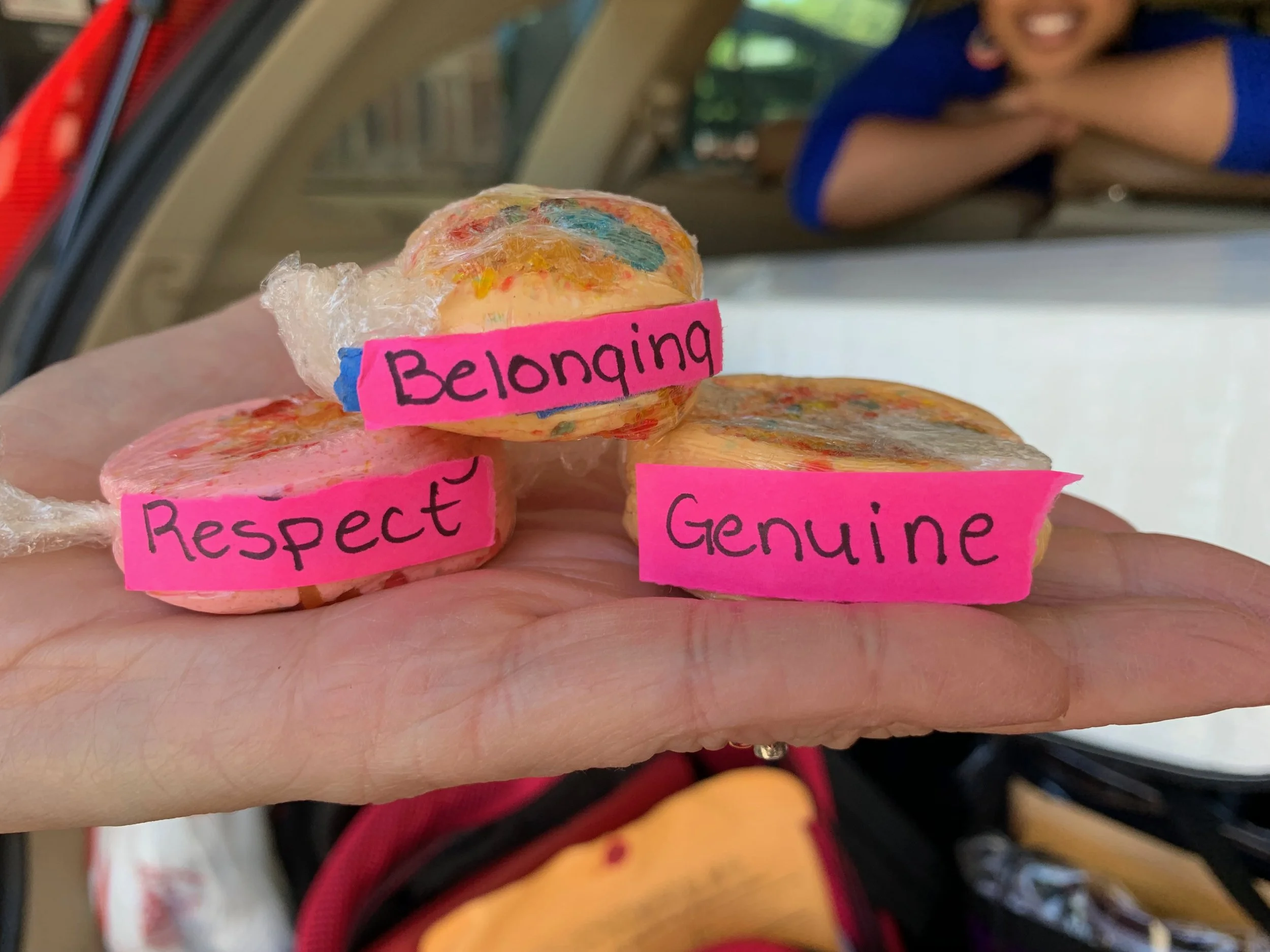

Homemade “care outreach tools” (taffies made of cornstarch, Jell-O powder, coffee creamer, and an inspirational word) made by a program participant for classmates who were just starting to work on trusting others.

Unfortunately, just as we were finishing the research and preparing to gear-up program improvement efforts, the Covid-19 pandemic exploded. The prison along with the rest of the world shut down all non-essential operations, and as has been widely reported, incarcerated people suffered greatly.

Our teaching program was not able to see students in person for nearly two years. However, due to both our relationship-building across stakeholder groups and the insights about community and continuity, we were able to continue a distance learning version of the program during the pandemic.

Teachers created packets that were delivered to incarcerated students every two weeks, and I designed weekly activity pages to help students find grounding in care for themselves and others during the shutdown.

This win may seem small—and in many ways it was. However, given the Georgia prison system’s disinclination from allowing any programming during the pandemic, it took significant logistical coordination and relational capital to achieve even this victory.

Covid created an epidemic of isolation in the already-harsh space of US prisons, and our program’s relative continuity was surely no panacea. Yet by strengthening ties among system stakeholders and highlighting the importance of program continuity, we were able to provide a measure of continued connection to the outside world during the crisis.

Impacts

Despite the significant interruptions from the pandemic, this project had meaningful impact in several key areas (not all foreseeable at the outset:

● A clear message about the importance of community-building and care among program students, leading to program re-focus, as well as advocacy for aligned approaches in other prison education programs. This finding has been shared in 2+ journal articles and presented at 7+ conferences, including for prison education audiences.

● Continuation of program in packet-based form during pandemic, and insights packaged for design strategy work with students whenever feasible (due to Covid’s impacts at an already structurally-weak institution, consistent access to the prison has been difficult even as the pandemic has subsided).

● 3 junior researchers given the opportunity to lead research activities and participate in analysis, advancing their careers in impact-focused research.