The Takeaway

Project & impacts: A first-of-its-kind study on the interconnections between spirituality, religion, and the mental healthcare experiences of low-income women with depression, delivering results directly to clinicians and helping establish the case for qualitative work in religion and health.

My role: I conceived of, designed, and led this project from end to end, including participant outreach and consultation with a cross-disciplinary research advisory team throughout the process.

Amplifying Maternal Mental Health System User Voices

Listening to Low-Income Mothers on Depression and Spirituality

Background

For a variety of disciplinary and cultural reasons, healthcare providers and researchers often overlook the rich, complex role that religious faith can play in patients’ lives. For mental health providers working with low-income mothers in particular, this oversight can mean missing a layer of complexity that may be crucial for patients’ recovery.

Moreover, as an early-career researcher I noticed that even when mental health professionals did pay attention to spirituality, it was often only studied in a quantitative or purely instrumental way. Did praying regularly lower a patient’s score on a depression index? Could church attendance serve as a “coping strategy” for individuals with depression?

These approaches, while not entirely unfounded, are driven by piecemeal, external understandings of how religion might be “useful” to recovery—rather than a holistic, user-centered curiosity about how communities understand the relationship between wellness and spirituality. Missing out on this richness can lead to mental health interventions that are at best ineffective, and often downright culturally offensive.

In essence, the relationship between maternal mental health and spirituality is generally driven by providers and researchers, not mental health system users. Because of this, clinical relationships don’t always live up to their full potential.

Design Challenge

How might we help mental health clinicians better understand the relationship between spirituality and depression among low-income moms?

Project Roles

Lead Researcher

Community Outreach Lead

Project Manager

Methods Used

User Research (interviews, surveys)

Stakeholder Engagement

Participatory Co-Design

Narrative & Thematic Analysis

Affinity Mapping

Presentations & Storytelling

Process

Recognizing this problem, as a Harvard Master’s student I sought out a research mentor and collaborators at Boston University. I conceptualized and designed the project with guidance from my mentor, and carried out all research recruitment and interviews.

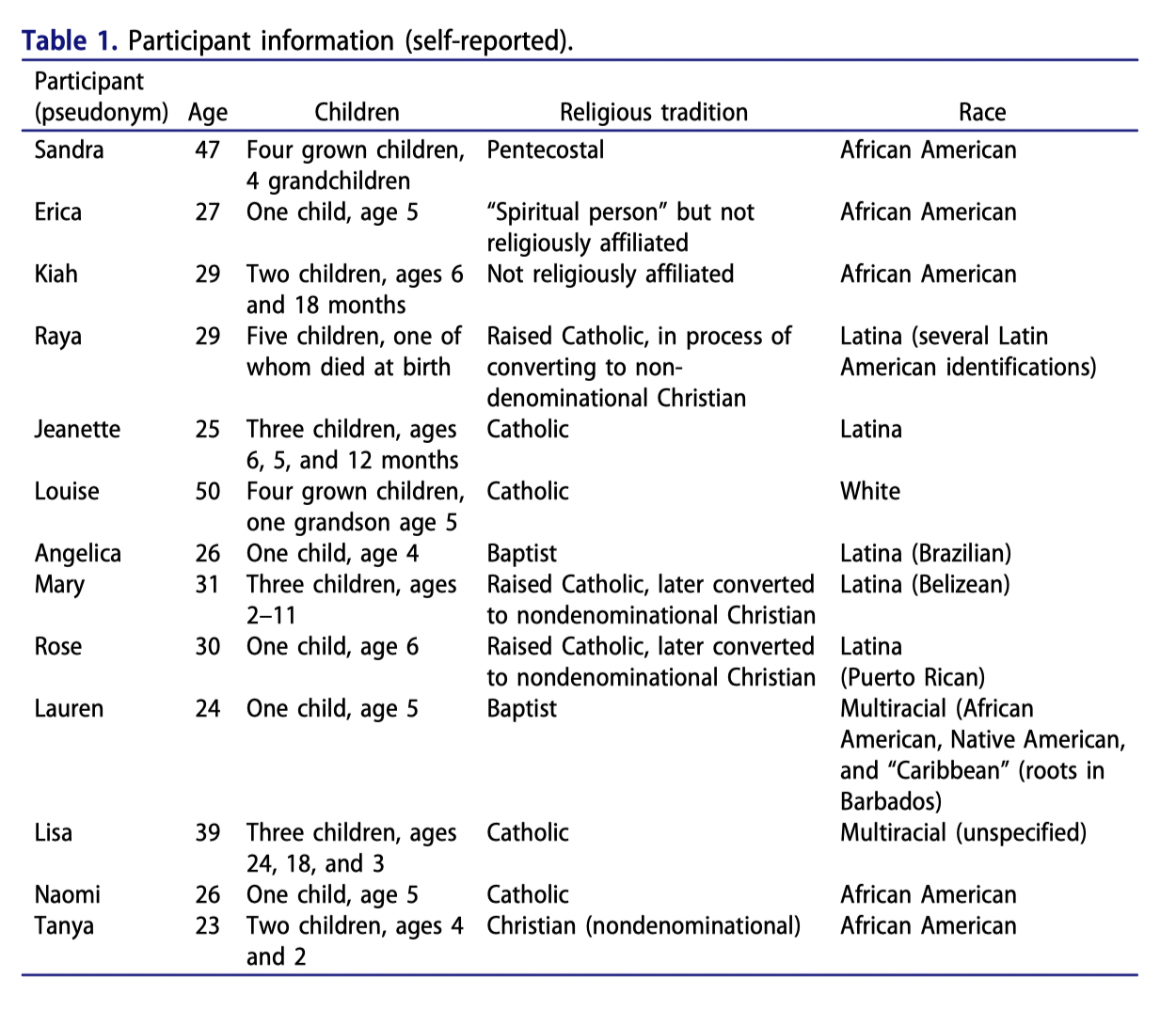

I did 13 contextual user interviews and administered 13 demographic and trauma-history surveys. The users were women who had been identified in another study as mothers with clinical depression, and who shared that some sort of spiritual or religious faith was a part of their life.

I recruited participants by phone and traveled to their homes for the interviews, choosing this approach because of the sensitive, stigmatized nature of mental health challenges and poverty. Often, this meant traveling across the city by multiple modes of public transit, to meet women in their own context and build a connection.

Choosing this approach meant that interviews were very time- and emotionally-intensive, but also, importantly, that women were open and vulnerable with me in ways that would not have been possible in public.

I recorded and then transcribed the interviews, and our team took turns thematically and narratively coding them. We also held eight ideation sessions to collaboratively identify themes and response strategies, and to check our findings against each woman’s narrative. Finally, I analyzed the results of our demographic and trauma-scale survey (at right, example from one of the published journal articles).

Our small team of three worked collaboratively on the analysis, ideation, storytelling and presentation phases of the project. I moved back and forth frequently between solo and collaborative work.

Findings: Three key takeaways for mental health providers

1)

Religion is a complex phenomenon in low-income women’s lives. Hearing a patient “is religious” should lead to further discussions, not assumptions about what faith means to her. Though our study was small, we heard stories of both agnosticism and supernatural apparitions; of church communities that healed and those that gossiped hurtfully; of a warm, encouraging God and of a God who had stepped back to let the world disintegrate. This richness cannot be captured on brief intake forms—clinicians should ask, and take the time to listen to the answers.

2)

Talk therapy must be coupled with other resources to respond effectively to the stressors of poverty. Some women expressed a level of frustration with therapy: how would it help them feed their kids, or afford their rent? Others expressed skepticism of whether care providers could really understand what they were going through. Our work therefore suggests that mental health care with low-income women will be most meaningful to users when it is coupled with other services (food, housing, medical assistance, etc.) to respond holistically to contextual causes of their depression.

3)

Clinicians should affirm patients’ strengths—including religious and spiritual resources that are helpful to them. This means more than encouraging practices like prayer and attending worship services. Rather, clinicians should familiarize themselves with the cultural, religious, and existential resources of the groups they work with. In our user population, for example, this would mean reading Black and Latina feminist theologies, the themes of which were echoed in many women’s narratives. By being attentive and curious in this way, clinicians are in better position to hear and support users as they draw on and develop their strengths as part of their recovery.

Impacts

This was a small, student-led project, but we achieved meaningful impact in three areas:

● Sharing results directly with clinicians. For example, hosting a meeting in which we shared our results with the medical research team that had initially connected us with potential participants. We shared our findings and recommendations for clinical practice and laid the groundwork for continuing partnership between our groups.

● Publishing in journals that clinicians read. The project yielded three academic articles, and we took care to publish in outlets with audiences in healthcare. We wanted to get our results and recommendations to people who could actually operationalize them. One paper in the Journal of Religion and Health has been cited 27 times, indicating significant readership and impact within the field.

● Helping to establish the importance of qualitative work on religion and health. Much of the research on spirituality and health is quantitative and survey-based. The complex narratives in this project provide a clear example of why religion is not fully quantifiable in this way, and why qualitative work must accompany quantitative if health system users’ full range of experiences are to be understood.